Blockchain Bites: Australia unwraps draft INFO225, Australia passes AML/CTF reforms for virtual assets, The end of yield stablecoins in the EU is nigh, UK Appeals Court rejects Wright’s (BTC and GenAI) hallucinations

06/12/2024

Steven Pettigrove, Jake Huang, Luke Higgins and Luke Misthos of the Piper Alderman Blockchain Group bring you the latest legal, regulatory and project updates in Blockchain and Digital Law.

Australia unwraps draft INFO225: Does your token offering cut the grass?

The highly anticipated draft update to the Australian Securities and Investment Commission’s (ASIC) Information Sheet (INFO 225) has been released alongside a consultation paper (CP 381), offering a glimpse into how the Australian regulator views the application of existing financial services laws to crypto-assets and related businesses (with a curious lawn mowing related example). The documents provide insight into ASIC’s interpretations of existing law and outline 13 practical examples of crypto-related offerings. ASIC is seeking feedback from industry to finalise this guidance, which is expected to be published by mid-2025. This is the first time that ASIC has sought industry guidance into a digital asset information sheet.

Industry feedback has been swift noting that:

- the proposed approach doesn’t provide clarity but provides an understanding as to how the regulator views the industry;

- remains focused on operational compliance with existing laws, and doesn’t tackle the fundamental issues and differences that digital assets pose;

- the proposed approach would dramatically increase compliance costs for Australian projects, which would likely send them offshore and leave Australian consumers exposed to whatever regulation applies there;

- reveals a position which if maintained would have “drastic consequences” for the industry.

It is important to remember at the outset that information sheets provide the regulator’s view of the law, they are not the law. However, the regulator has significant resources to test their view of the law and so this guidance is very useful for digital asset businesses deciding how they should structure.

What is new in the guidance?

In addition to providing some general guidance on the regulatory minefield that is financial products and financial services under Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), ASIC provides 13 specific examples of digital asset related offerings and how it sees these very detailed examples interfacing with existing financial services laws. The examples explore scenarios ranging from traditional securities issued on digital asset platforms (which no sensible person would argue are not caught by the Corporations Act) to more niche use cases (including a lawn mowing business with it’s own token?). Meanwhile, the paper does not meaningfully grapple with fundamental issues concerning token taxonomy and how decentralised systems can comply with existing laws.

The examples are below:

| Example 1 (exchange issued token) | Company A runs a digital asset exchange. They issue a digital asset where the relevant ‘white paper’ outlines it is to raise funds to assist in the development of the exchange. The token was marketed as a way of contributing to, supporting and potentially obtaining a financial return, or other benefit, by ‘investing in’ the project, and at least some consumers bought the tokens on that basis. The token’s price on the exchange (and on any other exchange) was expected to and does go up and down based on the perceived success of, and general sentiment towards, Company A’s exchange. The white paper stated that Company A intends to (but is not obliged to) buy back the tokens at a certain price if Company A’s exchange achieves certain success metrics (e.g. based on revenue, trading volume and profit). Company A’s digital asset is likely to be a facility for making a financial investment. It involves members of the public contributing money or money’s worth which is used in a business project where both the business and the investors intend the money to be used to generate a financial return (e.g. the token increases in value and the token is intended to be bought back by the exchange if the project is successful). The investors do not have day-to-day control over how the funds are used (even if there is a voting mechanism to consider certain matters). |

| Example 2 (staking services) | Company B runs a digital asset exchange. It offers its customers the ability to ‘natively stake’ certain native digital assets to support verification of blockchain transactions, where the blockchain uses a ‘proof of stake’ consensus mechanism. Company B markets its staking services as a way of earning a return on otherwise idle digital assets. Company B takes a small share of the staking revenue as a fee for providing the services. For all digital assets made available to stake, Company B allows customers to stake with no minimum balance, withdraw their staked assets instantaneously, and participate in staking at any time. However, the underlying processes for staking on the relevant blockchains have restrictions, such as: • a minimum staking balance • the digital assets must be locked for a minimum period of time, or there is an inbuilt delay in returning unstaked assets, and • limits on the number of individuals who can participate in staking at one time. Company B’s facilities for staking these digital assets are likely to be facilities for making a financial investment (and potentially managed investment schemes). This is because in each staking facility there is a contribution of money’s worth (being the digital asset) which is pooled or used in a common enterprise by Company B to generate a financial return or other benefit for the investor, and the investors do not have day-to-day control of the facilities. In each facility, the rights and benefits from Company B’s facility differ from and exceed what the client would get if they undertook to stake the digital assets without the services of Company B. For example, Company B’s facilities allow clients to stake digital asset balances below the minimum for that particular blockchain. |

| Example 3 (in-game NFTs) | An online gaming company, Company C, develops a game that uses a public blockchain to store and record ownership of in-game items that can be purchased (with digital assets or fiat currency) or received by playing the game. These are marketed as limited edition or unique items, that are both collectables and can be used in the game. These non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are used as ‘skins’ to change the appearance of in-game characters or items used by such characters for in-game play. The NFTs are first sold, or received over time through success in playing the game, to players by Company C. The NFTs are also tradeable on secondary markets and the prices of the NFTs can change based on buyer and seller interest. Company C does not make any comments or representation in their white paper or marketing materials that the contribution used to buy the NFTs will be used to generate a financial return, or other benefit, for the player (other than the utility of playing the game) or that the NFTs should be bought because of an expectation that the prices will increase. The NFTs are unlikely to be a facility for making a financial investment because the contributions are not, nor are they intended to be, used to generate a financial return, or other benefit for the customer. There is also no suggestion that the customer intended their contribution to be used for that purpose, even if some bought an NFT for speculative purposes. |

| Example 4 (yield-bearing stablecoins) | Company D issues a digital asset which is marketed as a yield-bearing stablecoin. They state that the digital asset token is expected to maintain a stable price and value in Australian dollars (AUD). Company D uses the funds raised from the sale of the token to purchase a range of bank deposits and Commonwealth Government Securities, and holds these assets on trust. Holders of the token have a right to redeem their tokens for Australian dollars. Company D states that the stable value of the token will be achieved by linking the token to assets held in the trust. The token is marketed as a ‘yield-bearing stablecoin’ that earns ‘yield’ through holders receiving new tokens over time based on the returns generated from the trust assets. New tokens are issued to existing holders based on the returns generated from the underlying assets (less the fees and costs of running the fund), providing a financial return to holders. A large number of investors buy the token because of the proposition of a stable value and that it also offers a return. These tokens are a useful way to ‘hold funds’ while waiting to make other digital asset investments, and also as a way to settle digital asset transactions or participate in decentralised finance arrangements. Company D’s digital asset is likely to be an interest in a managed investment scheme. Investors receive a token for contributing money or money’s worth, that contribution is pooled together and the investors do not have day-to-day control over the operation of the scheme. The funds contributed generate several benefits, which can be financial benefits and benefits consisting of rights or interests in property. For example, a token that is stable in value and is able to be used for making payments has benefits over other tokens that have highly volatile prices. |

| Example 5 (asset-linked tokens) | Company E issues a gold-linked digital asset token. They promote the token as having a price that is linked to the price of gold. In practice, the price of the tokens in the secondary market does seem to generally track the price of gold. Company E uses the money raised from token sales to purchase spot gold and other goldrelated investments (e.g. financial products such as gold-related futures and options), and holds them in a trust. Each token represents an interest in the trust holding the gold or gold-related assets. Company E’s digital asset token is likely to be an interest in a managed investment scheme. Investors contribute money which is pooled to purchase gold and gold-related assets. While the gold-linked token may not generate cash flow, it has the potential for capital gains based on changes to the value of the underlying gold assets, which is a financial benefit. Investors also do not have day-to-day control over the use of the funds. |

| Example 6 (tokenised memberships) | Company F runs a business selling books to the general public. They offer a membership program to customers that, for a fee, gives the customer access to member-only events and discounts. Membership is recorded on a public blockchain, through ownership of an NFT. The tokens are tradeable. The digital asset token issued by Company F is unlikely to be a managed investment scheme. While Company F uses the money or money’s worth raised from selling the memberships for its business, the contributions are not used to generate financial benefits for the members. |

| Example 7 (tokenised receipt for the future provision of services) | Company G operates a lawn mowing business. It has issued digital assets to pre-sell their services to grow their business. A holder of one token is entitled to have one square metre of grass mown on one occasion. The tokens are tradeable. Company G undertook an initial token sale to distribute the tokens. There is currently a fixed supply of tokens, and Company F has made representations that they will not issue any further tokens. In issuing the tokens to the public, Company F outlined that they intend the proceeds from the token sale to fund the development of the business. While the tokens are tradeable and the price can fluctuate, each token remains redeemable for the same amount of future service. The fluctuations in the token’s price could be attributable to the popularity of the service as the business grows and the number of similar competing businesses in the locality. The digital asset issued by Company G is unlikely to be a managed investment scheme. While Company G uses the money’s worth raised for its business, the contributions are not used to generate financial benefits for the members (i.e. the benefits for holders attributable to each token are largely fixed). |

| Example 8 (native token) | Company H is seeking to establish a new blockchain. They issue an initial token (H1) to raise funds from supporters. H1 is intended to be time-limited, and supporters receive one H1 token per AUD of value contributed, whether they provide fiat currency or digital assets. In the white paper, Company H states that when the new blockchain is operational, H1 tokens will be cancelled and holders will be given new tokens (H2) equal to the number of H1 tokens they hold. Company H intends the new H2 tokens to have ongoing use in the new blockchain ecosystem (e.g. to pay transaction fees) and they will be tradeable. The H2 tokens are expected by the social media followers of the project to begin trading at more than $1 per token. After 12 months, the blockchain launched. The H1 tokens were cancelled and holders were given H2 tokens as promised. On initial launch, additional H2 tokens were available to the general public for purchase for $2 each from Company H’s treasury. The process for operating the blockchain also means new H2 tokens are issued over time as people contribute effort and work to process transactions and secure the network. The H2 tokens are popular and increase in value over time (due to Company H’s ongoing development of new functionality). The initial fundraising involving the H1 tokens is likely to be a managed investment scheme. Initial supporters contributed money or money’s worth which was pooled by Company H to be used in the common enterprise of developing the blockchain enterprise. Contributors did not have day-to-day control of the enterprise and expected to receive valuable benefits at the end (the H2 tokens). Whether or not the new H2 token is a managed investment scheme would depend on whether money or money’s worth contributed to acquire the H2 token (whether from the return of the H1 tokens from the initial fundraising, later purchases or otherwise) is pooled or used in a common enterprise to be used to generate a financial benefit to holders of the H2 token, where the holders of the H2 token do not have day-to-day control of the enterprise. |

| Example 9 (meme coins) | A private individual (Ms I) issues a ‘meme coin’ token named after a well-known historical figure. The money collected is not used in Ms I’s business or for any other commercial enterprise. The coin does not provide holders with any rights. While the price of the coin goes up and down, it is not connected with the success or otherwise of Ms I’s (or anyone else’s) business. Ms I’s coin is not affiliated with any particular blockchain or digital asset exchange and is not promoted as a method of making payments or pay transaction fees. Ms I’s coin is unlikely to be a security or any other type of financial product, such as a facility for making a financial investment. While it does involve the potential for capital gain (a type of financial return), there does not appear to be a sufficient connection between the use of initial funds raised and any potential capital gain, nor does any potential capital gain appear to be linked to the efforts of the issuer. |

| Example 10 (tokenised tickets) | Company J issues a tokenised concert ticket. The holder of the token is entitled to general admission seating to a major upcoming concert event in Sydney. The token is transferable and whoever holds the token at the time of the concert is able to enter the venue. The price of the token does increase somewhat in the lead up to the event, which is sold out. The token is not able to be used to make payments generally and it does not carry any other entitlements. Company J’s concert token is unlikely to be a security or any other type of financial product, such as a facility for making a financial investment. While it does involve the potential for capital gain (a type of financial return), there does not appear to be a sufficient connection between the use of initial funds raised and any potential capital gain, nor does any potential capital gain appear to be linked to the efforts of the issuer. |

| Example 11 (tokenisation) | Company K provides the service of helping corporate entities issue corporate bonds (debentures) on a blockchain. This ‘tokenisation’ involves a range of processes that means the blockchain records the holdings of the bond. The bonds have the typical features of a traditional bond, such as a promise to repay principal and to pay interest. The tokenisation does not result in fractionalisation of the bonds. The tokenised bonds issued are likely to be a debenture (and, therefore, a security). Whether or not Company K requires a licence from ASIC will depend on the range of services they offer |

| Example 12 (derivatives) | Company L offers contracts that allow a client to speculate in the change in value of an underlying digital asset (with or without leveraged returns). Clients do not actually acquire an interest in the underlying digital asset but they can make or lose money depending on whether the price of the underlying digital asset goes up or down. The contracts offered are likely to be derivatives. |

| Example 13 (non-custodial wallet and stablecoin) | Company M offers a non-custodial digital asset wallet service and issues their own proprietary stablecoin token on a public blockchain. The digital asset wallet service allows a client to instruct Company M to transfer their token to another address or digital asset wallet issued by Company M. The service can also be used to transfer the token to any other address or digital asset wallet that accepts these tokens. Company M markets this service as a convenient way for its clients to make payments to third parties. Company M’s digital asset wallet service itself is likely to be a non-cash payment facility. It is a facility through which clients can and do make payments to third parties, using Company M’s token or other tokens, and Company M’s marketing promotes the wallet as having that functionality. |

In summary:

- Certain examples clearly engage existing laws, such as examples 1, 2, 4, and 12. The application of the law in these examples more or less tracks industry practice.

- However, some examples highlight grey areas. For instance, how will “exchange tokens” issued as part of loyalty programs or pass-through staking services which match underlying blockchain staking be characterised? It would have been helpful if the examples address some of the features and indicate treatment if those features change.

- Notably, meme coins and in-game NFTs are deemed outside the scope of current financial services laws, which is interesting given the huge rise in memecoins of late.

- As outlined in example 13, digital asset wallets are considered by ASIC to fall under financial services regulation as a facility for making non-cash payments, reflecting recent enforcement actions and judicial trends, such as the Qoin judgment, but the example appears confused, if the wallet is non-custodial but allows payments to be made by a company, then the payments themselves are likely to be a non-cash payment facility, but the purely non-custodial wallet element seems outside this definition unless the only way a payment can be made is via the issuer.

While these examples provide some clarity on the specific examples, real questions remain around their practical application and how well they reflect real-world offerings in the Australian ecosystem. ASIC invites feedback on whether some digital assets may still sit outside these categories.

Safe harbour proposals

For operators engaging in financial services with digital assets that may now be deemed financial products under the updated guidance, ASIC is proposing a ‘safe harbour’ framework. This would allow businesses to apply for Australian Financial Services Licences (AFSL) or market licences without the immediate risk of enforcement action, provided they meet certain conditions and timelines.

Interestingly, existing licensees are essentially ‘grandfathered’ into the framework, with ASIC maintaining that no substantial regulatory changes are needed to accommodate digital assets. This position is likely to be challenged given that ASIC’s starting point some ten years ago concerning digital assets was that they were not financial products. On the other hand, startups and new entrants must seek licensing, raising questions about competition and fairness and whether this approach creates a regulatory advantage for established players.

The balance between enabling responsible innovation and ensuring a level playing field will be critical, and industry input is crucial to shaping these policies.

Wrapped tokens and stablecoins

ASIC has also weighed in on the regulatory treatment of stablecoins and wrapped tokens:

- Stablecoins: ASIC’s view is that non-yield-bearing stablecoins pegged to fiat currencies may still be classified as non-cash payment facilities (NCPF). ASIC’s guidance reflects concerns around how these tokens are structured, marketed, and backed by financial obligations on issuers. ASIC’s proposal appears to be that stablecoins will be regulated under existing laws until such time as payment stablecoin legislation comes into effect.

- Wrapped tokens: ASIC’s view is that wrapped tokens may be considered derivatives, given their reliance on the value of underlying digital assets and their redemption features.

Looking forward

ASIC acknowledges that the documents do not represent final policy and seeks feedback from industry on the compliance costs, impacts to competition, and wholistic cost/benefit considerations.

The consultation period closes on 28 February 2025, with the finalised guidance expected by Q2 2025. It is difficult to say if this timeline will be impacted by an upcoming federal election. In the meantime, the regulator continues to encourage businesses and operators to seek professional advice to understand their obligations and navigate the evolving regulatory landscape.

Written by Steven Pettigrove and Luke Higgins

Australia passes AML/CTF reforms for virtual assets

The Australian Parliament has passed the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Amendment Act 2024 (the Act) introducing significant reforms to combat financial crime. The legislation aims to modernise Australia’s Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing (AML/CTF) framework, aligning it with international standards set by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Act outlines three primary objectives of:

- to extend the AML/CTF regime to certain higher-risk services provided by real estate professionals, professional service providers including lawyers, accountants and trust and company service providers, and dealers in precious stones and metals—also known as ‘tranche two’ entities;

- to improve the effectiveness of the AML/CTF regime by making it simpler and clearer for businesses to comply with their obligations; and

- to modernise the regime to reflect changing business structures, technologies and illicit financing methodologies.

Modernising the framework

The 2024 amendments reflect technological advancements and emerging risks, particularly in the virtual asset sector. The legislation replaces the term ‘digital currency’ with ‘virtual assets’, broadening the scope of AML/CTF laws to cover a wider array of transactions involving digital assets and with the intention of ensuring coverage of stablecoins, utility tokens, governance tokens and non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

The Act defines a ‘virtual asset’ as:

(1) a digital representation of value that:

(a) functions as any of the following:

(i) a medium of exchange;

(ii) a store of economic value;

(iii) a unit of account;

(iv) an investment; and

(b) is not issued by or under the authority of a government body; and

(c) may be transferred, stored or traded electronically.

(2) A virtual asset is a digital representation of value that:

(a) enables a person to vote on the management, administration or governance

of arrangements connected with a digital representation of value; and

(b) is not issued by or under the authority of a governing body.

(3) A virtual asset is a digital representation of value of a kind prescribed by the AML/CTF Rules

The definition of ‘virtual assets’ excludes money, digital representations of value used exclusively within electronic games, customer loyalty or reward points, digital representations of value similar to electronic game assets or loyalty points that are not intended by the issuer to be convertible into another digital representation of value or money and digital representations of value prescribed by the AML/CTF Rules.

The legislation also introduces new designated services within the virtual asset sector, including:

- exchanges between one or more forms of virtual assets;

- certain virtual assets transfers on behalf of a customer (subject to the AML/CTF Rules);

- virtual asset safekeeping services; and

- participation in and provision of designated services involving the offer or sale of virtual assets.

Virtual asset safekeeping services are defined broadly and intended to cover multi-signatory arrangements. According to the Explanatory Memorandum, this would include services having the ability to hold, trade, transfer or spend the virtual asset per the owner or user’s instructions. Persons who solely provide a software application (such as software developers) and ancillary infrastructure providers like cloud solutions are said to be excluded.

virtual asset safekeeping service:

(a) means a service in which virtual assets or private keys are controlled or managed for or on behalf of a person (the customer) or another person nominated by the customer under an arrangement between the provider of the service and the customer, or between the provider of the service and another person with whom the customer has an arrangement (whether or not there are also other parties to any such arrangement)

The changes also contemplate that AML/CTF compliance obligations (including reporting obligations) will cover transfers of value broadly, such as electronic funds transfers and transfers of virtual assets.

Following the EU’s planned implementation of the travel rule, the Act introduces the rule for virtual asset transfers, subject to certain carve-ours and some flexibility to adapt specific requirements to facilitate compliance.

VASPs will also need to take steps to identify self-hosted wallets and report transactions to unverified self-hosted wallets to AUSTRAC.

Professional services firms will also have requirements to comply with AML/CTF laws in relation to certain dealings and transactions involving virtual assets.

The changes for virtual asset service providers will take effect by 31 March 2026.

The reforms will see the term DCE replaced by VASP as Australia’s AML/CTF laws come into closer alignment with global standards.

They will involve substantial changes for DCEs who fall within the existing regime as well as bringing many new entity types within the AML/CTF regime for the first time. This will mean a busy 18 months as DCEs look to uplift their existing policies and procedures while grappling with new reporting and compliance obligations. For others, it will mean applying to AUSTRAC to become enrolled as a VASP for the first time and likely backlog as AUSTRAC begins to process applications across a range of industries. We expect more news from AUSTRAC on these transitional arrangements in the coming months.

Written by Steven Pettigrove, Luke Misthos and Emma Assaf

The end (of yield stablecoins in the EU) is nigh!

As the EU’s MiCA comes into effect the challenges of regulation hitting innovative projects is starting to show, with Tether announcing they are discontinuing their EUR denominated stablecoin, with users to exit by 27 November 2025, and Coinbase ending their yield bearing USDC stablecoin in the EU.

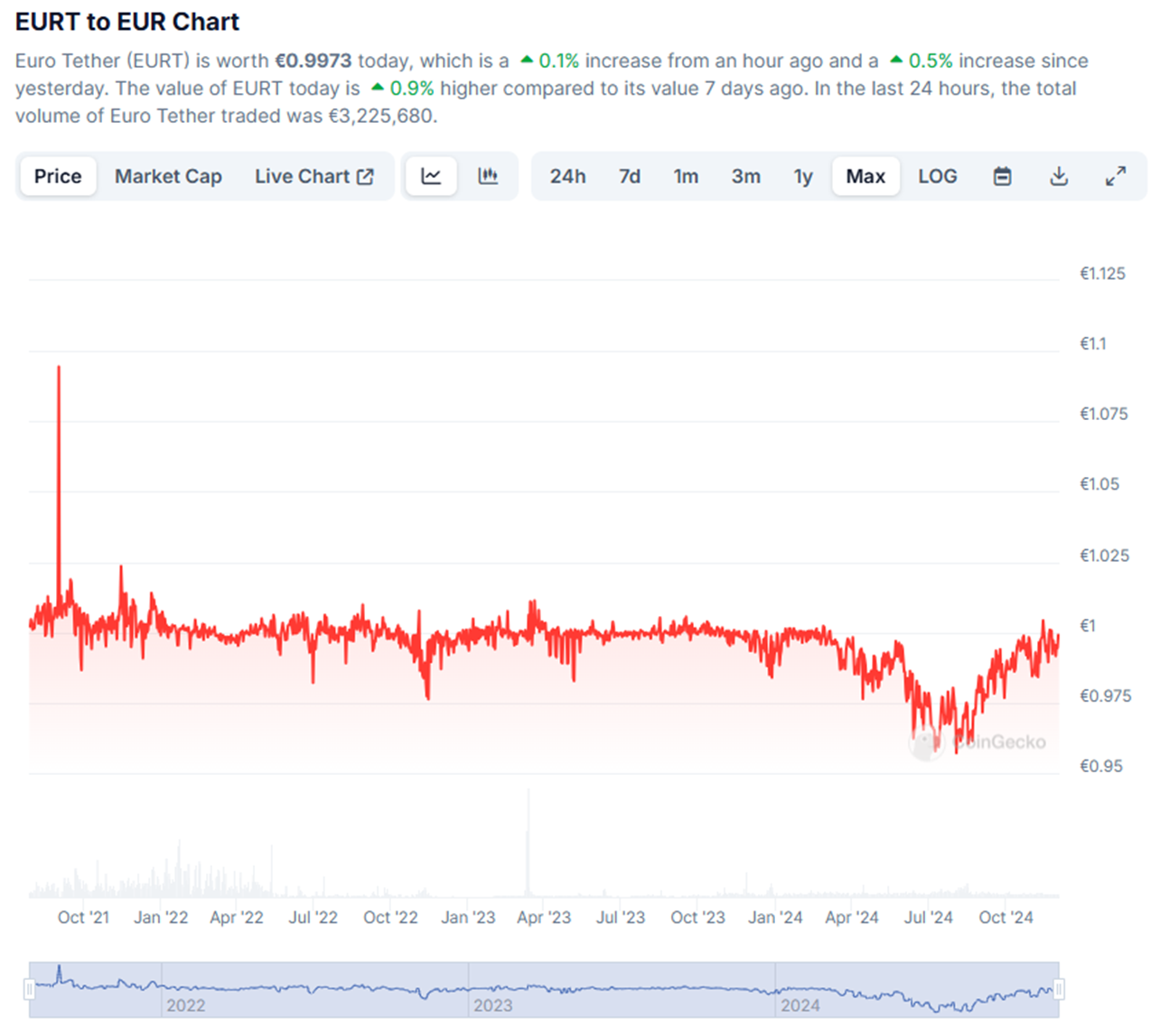

Stablecoins such as Tether hold (or allegedly hold given the various concerns about Tether over the years) dollar for dollar backing for the stablecoins they issue. Those backing reserves can earn very substantial interest returns, with Tether earning USD$7.7B this past year from their reserves). Tether’s EURT has maintained a decent price peg against the Euro but has suffered some small discounting over the last year, possibly MiCA induced:

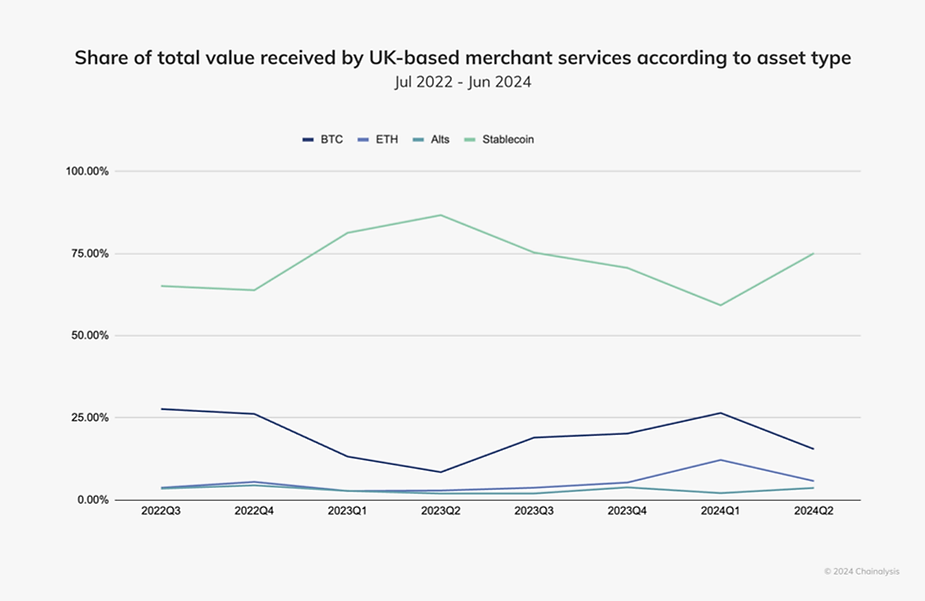

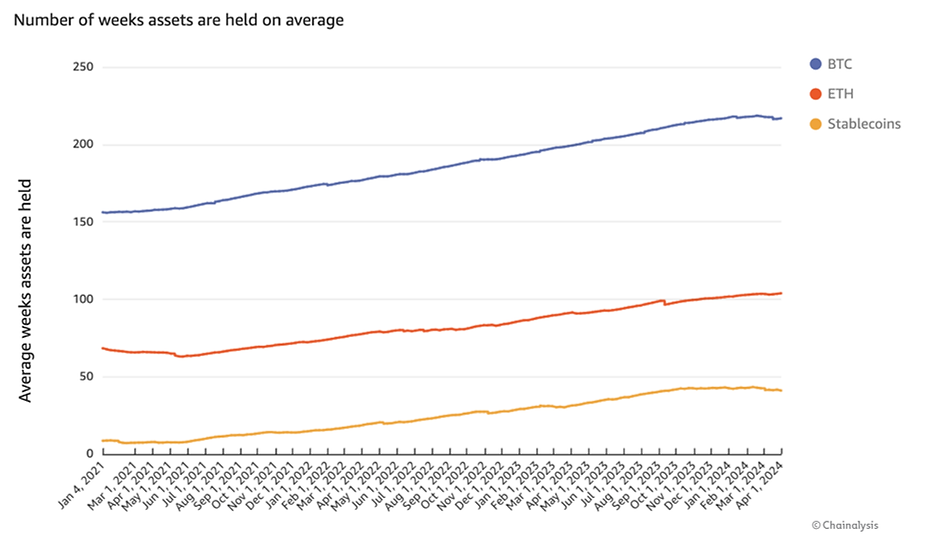

Coinbase offers “rewards” which weren’t expressly linked to their underlying reserves, but are largely viewed as funded by interest earned on reserves. Chainalysis has conducted research into stablecoin usage, which continues to rise and found that stablecoins dominate holdings in western europe and are being held for longer on average over time:

Source: MiCA’s Stablecoin Regime and Its Remaining Challenges: Part 1

As a result the MiCA regime is likely to have significant impacts on this very popular form of cryptocurrency.

MiCA Stablecoin Regulation

The specific issue is this, Article 50 which prohibits the granting of interest.

More broadly, the MiCA regulation in the EU recognise two general categories of tokens:

- e-money tokens (EMTs) which are designed to serve primarily as a means of payment; and

- asset-referenced tokens (ARTs) which aim to maintain a stable value by having their price pegged to certain assets.

Issuers of EMTs must have a licence as an authorised credit institution or electronic money institution to offer stablecoins (something Circle has done) and are subject to oversight by the European Banking Authority. Most stablecoins are expected to fall under the EMT category. By contrast issuers of ARTs must be approved by a competant supervisory authority in an EU member state or could be exempt from that requirement if issued by a licensed credit institution. Issuers have to publish a whitepaper including details of:

- specified details of the issuer and a description of the nature of the project;

- the rights and obligations attached to the token;

- the nature of the underlying technology used for the token; and

- identification of risks the issuer anticipates could arise from the issuance of the token, these are likely to include bankruptcy risks, financial stability risks, and anti-money laundering and counter terrorism financing risks (pus others).

There are ongoing regulatory requirements to maintain reserves and custody arrangements and segregation of assets with reporting requirements and governance arrangements to identify and manage the key risks.

Given Tether’s history it’s not a surprise that they would need to migrate to a different issuance structure, but there has also been anger at the new rules requiring an end to yield bearing stablecoins, which users purchased to earn while holding. X users mocked the decision, including:

What’s next?

Despite the rules, further stablecoins are planned, and it will be interesting to see how yields from the underlying reserves can find their way back to holders given that is clearly something the market, and issuers, wish to do. In the meantime the slow progress of regulation means that even if the EU wishes to permit yield on stablecoins (which is no guarantee), it will take sometime before it could be enabled.

Written by Michael Bacina and Steven Pettigrove

UK Appeals Court rejects Wright’s (BTC and GenAI) hallucinations

Craig Wright’s legal woes continue as the UK Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal in a claim brought by the Crypto Open Patent Alliance (COPA). Wright had sought to challenge an earlier judgment that definitively concluded he is not Bitcoin’s creator, Satoshi Nakamoto—a claim central to his ongoing legal battles. The Court, led by Lord Justice Arnold, described Wright’s arguments as baseless, stating they had “no prospect of success” and “totally without merit.”

Allegations of Judicial Bias Rejected

In his appeal, Wright alleged bias against the trial judge, a claim thoroughly dismantled in the decision. The Court found “no credible allegation of either actual bias or apparent bias” and noted that Wright’s arguments amounted to disagreements with the judge’s reasoning rather than evidence of partiality. In fact, the ruling emphasised that the judge had “leant over backwards to ensure that Dr Wright received a fair trial.”

AI-Generated Arguments Undermine Credibility

Notably, Wright’s reliance on ChatGPT raised further questions about his legal strategy. The court observed that parts of Wright’s appeal contained “multiple falsehoods, including reliance upon fictitious authorities […] which appear to be AI-generated hallucinations.” This misuse of generative AI underscores the unconventional and increasingly dubious nature of Wright’s legal approach.

Contempt of Court Hearing Looms

Wright’s legal troubles aren’t over yet. He is scheduled to appear in court on December 18 for a contempt hearing related to COPA’s counterclaim against his staggering £900 billion ($1.14 trillion) lawsuit against Jack Dorsey’s Square and BTC Core. If found guilty, Wright could face arrest and up to two years in prison.

This latest defeat further cements Wright’s unenviable position in the crypto world, as his claims and tactics continue to unravel under judicial scrutiny.

Written by Steven Pettigrove and Luke Misthos