Blockchain Bites: RBA announces strategic commitment to wholesale CBDC work, Australian misinformation bill stirs free speech debate, SEC cans ‘wild-caught’ NFT membership, SEC flips on the phrase “crypto-asset securities” with no definition

20/09/2024

Michael Bacina, Steven Pettigrove, Jake Huang, Luke Higgins and Luke Misthos of the Piper Alderman Blockchain Group bring you the latest legal, regulatory and project updates in Blockchain and Digital Law.

RBA announces strategic commitment to wholesale CBDC work

At the Intersekt Fintech Conference in Melbourne today, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) announced its strategic commitment to prioritize its work agenda on wholesale digital money and infrastructure, including a wholesale central bank digital currency (CBDC) over a retail CBDC. These efforts follow the RBA’s successful CBDC pilot in 2023 with a view to unlocking the potential efficiency benefits of tokenised assets and markets for the Australian economy.

Brad Jones, Assistant Governor (Financial System) of the RBA, spoke on financial innovation and the future of CBDC in Australia, coinciding with the RBA and the Treasury’s first-ever joint paper released today on CBDC and the future of digital money in Australia.

Mr Jones said,

the RBA is making a strategic commitment to prioritise its work agenda on wholesale digital money and infrastructure – including wholesale CBDC – rather than retail CBDC.

According to Jones, the RBA assessed the potential benefits as more promising, and the challenges less problematic, for a wholesale CBDC compared to a retail CBDC.

Unlike a retail CBDC that would be issued for use by the public, a wholesale CBDC would, according to Mr Jones:

represent more an evolution than revolution in our monetary arrangements.

Mr Jones said the RBA is committing to a three-year applied research program on the future of digital money in Australia, of which the most immediate priority is to launch a new project with industry on wholesale CBDC and tokenised commercial bank deposits.

Roadmap

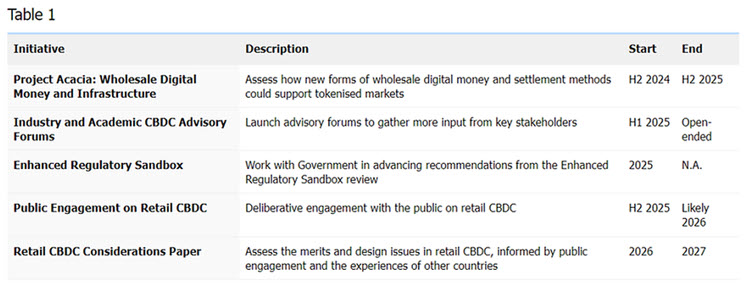

While the RBA will focus its resources on a wholesale CBDC, it appears that a retail CBDC is not off the table depending on global developments. The following table sets out the key components of the three-year digital money work plan for the RBA and Treasury:

According to this work plan:

- Top priority is to launch the public phase of Project Acacia, which builds on the lessons from RBA’s CBDC pilot last yearby focusing on opportunities to uplift the efficiency, transparency and resilience of wholesale markets through tokenised money and new settlement infrastructure. In October, the RBA will publish a consultation paper inviting industry engagement.

- To launch industry and academic CBDC advisory forums in the first half of 2025, covering both retail and wholesale CBDC issues.

- A third initiative, to begin in 2025, will involve supporting reforms to a existing regulatory sandbox – which provides unlicensed businesses scope to test new financial products and services for a limited time – for financial innovation, including digital money and infrastructure.

- A fourth initiative commencing later next year may involve a series of ‘deliberative workshops’ on retail CBDC with the Australian community. Focus groups could include a broad cross-section of the population as well as minority groups that can be under-represented in public policy consultations.

- Finally, the RBA and Treasury are committed to reassessing the merits of a retail CBDC over time, with a follow up paper to be published in 2027.

Retail CBDC considerations

As mentioned above, Mr Jones said RBA considers the potential benefits of a retail CBDC generally appear modest or uncertain at the present time, relative to the challenges it would introduce.

He followed that most of the arguments made internationally in support of a retail CBDC (e.g. in relation to efficiency and cost, financial inclusion, bank runs, monetary policy implementation and transmission) reflect issues that are either of limited relevance to Australia, or where it is not obvious that a retail CBDC would best address them.

Wholesale CBDC considerations

Mr Jones acknowledged the context in which the RBA considers wholesale CBDC is fundamentally different to retail CBDC because central banks already have a long history of issuing digital money to financial institutions in support of their monetary and financial stability objectives.

Like Exchange Settlement (ES) balances, a wholesale CBDC would be issued to eligible financial institutions and serve as the ultimate safe asset in the settlement of wholesale market transactions. What is new is that it could exist on different types of ledgers (centralised or decentralised) possibly alongside tokenised assets, and offer greater functionality than today’s ES balances. This could support asset settlement and other wholesale payments in new ways.

Wholesale CBDCs may play a role to uplift the functioning of wholesale markets, including by:

- Reducing counterparty and operational risks, and improving capital efficiency, by freeing up collateral

- Increasing informational transparency and auditability

- Increasing liquidity and the ability to transact

- Reducing intermediary and compliance costs

Tokenisation

Mr Jones also mentioned that the RBA’s exploratory research has seen the potential role that tokenisation might play in a future financial system:

Tokens could be stored, traded and transferred on either centralised or decentralised programmable platforms. The programmability of tokens via smart contracts, and the ability to free up collateral and reduce counterparty risk by atomically exchanging money and assets on the same ledger, have been of particular interest in experimental research.

Conclusions

According to the RBA, the introduction of a wholesale CBDC may require supporting legislation depending on the design and scope of use. The RBA and Treasury have expressed reluctance to compromise any CBDC design features in an effort to give it legal status under current legislative or regulatory frameworks. Instead, they believe it is preferable to identify the features of a CBDC that are most desirable from a policy perspective, and then make any necessary enabling amendments to applicable legislation.

While the RBA’s plan to focus on a wholesale CBDC puts a retail CBDC on the backburner for now, a wholesale CBDC could still unlock significant opportunities for the private sector in relation to tokenised assets and stablecoins. Reuters reported that around 134 countries representing 98% of the global economy are now exploring digital versions of their currencies, according to a recent research by a US think-tank. Following the RBA and the Treasury’s announcement, Australia will follow in the footsteps of other major economies such as the US and China in what might be the biggest financial innovation in decades.

Written by Jake Huang and Steven Pettigrove

Australian misinformation bill stirs free speech debate

The Australian Government has introduced a Bill to Parliament on combatting seriously harmful misinformation and disinformaton on digital platforms, but stirring public debate on whether the proposed legislation could erode free speech.

The government said the Communications Legislation Amendment (Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation) Bill 2024 is focused on combatting the most seriously harmful content on digital platforms, and contains strengthened protections for freedom of speech.

The government explained their rationale for the Bill:

While digital platforms have brought significant benefits to Australians – allowing us to connect with family and friends around the world, they can also serve as a vehicle for the spread of misleading or false information that is seriously harmful to Australian’s health, safety, security and wellbeing.

According to the Australian Media Literacy Alliance, 80% of Australians say the spread of misinformation on social media needs to be addressed.

The Bill will:

- empower the Australian Communication and Media Authority (ACMA) to oversee digital platforms with new information gathering, record keeping, code registration and standard making powers;

- introduce new obligations on digital platforms to increase their transparency with Australian users about how they handle misinformation and disinformation on their services;

- will complement voluntary industry codes but allow ACMA to approve an enforceable industry code or make standards should industry self-regulation fail to address the threat posed by misinformation and disinformation.

The government has emphasised that nothing in the Bill enables ACMA themselves to take down individual pieces of content or user accounts,

Platforms are and will remain responsible for managing content on their services in line with their own terms of service.

However, the Bill and its previous version has attracted criticism and concerns from legal experts and human right organisations around its potential to undermine free speech. The Australian Human Rights Commission expressed these concerns in its submission to a previous draft of the Bill, which concerns still apply with regards to the latest draft,

The first issue is the overly broad and vague way key terms – such as misinformation, disinformation and harm – are defined. Laws targeting misinformation and disinformation require clear and precise definitions.

The second key problem is the low harm threshold established by the proposed law. Content that is “reasonably likely to cause or contribute to serious harm” risks being labelled as misinformation or disinformation.

The fourth concern relates to the powers to regulate digital content that are granted under the draft bill to digital platform providers and (indirectly) the ACMA…There are inherent dangers in allowing any one body…to determine what is and is not censored content. The risk here is that efforts to combat misinformation and disinformation could be used to legitimise attempts to restrict public debate and censor unpopular opinions.

As the Australian Human Rights Commission points out, it is challenging to strike the right balance between combating misinformation or disinformation and protecting freedom of expression. While the government’s proposal seeks to tackle the real and present threat posed by misinformation, the Bill’s effectiveness in tackling this objective while remaining consistent with core democratic values remains to be debated.

Written by Jake Huang and Steven Pettigrove

Endangered tuna? SEC cans ‘wild-caught’ NFT membership

Crypto and blockchain have promised many new innovations and business ideas, and amidst the claimed scams and cash-grabs of the ICO boom and roaring (then falling) NFT market, one project stood out as providing an innovative use-case for NFTs as a tradeable membership token, similar to how fans can presently procure season tickets or (if they are rich enough, debenture seats in stadiums, and potentially enable leasing out or transfers of those membership with lower costs than has occurred before.

We wrote it up at the time and said that:

The membership opportunities for NFT holders to interact as part of an exclusive club are only just starting and more experiments of this kind are sure to come.

The basic idea was that two different NFT tokens would entitle holders to different special access at the restaurant, including for private dining. The sale netted US$14.8M for the sellers and some NFTs were retained future sale, and with a plan for additional clubs, offerings and social experiences. Unfortunately, the US Securities and Exchanges Commission has, in the words of dissenting Commissioners Peirce and Uyeda:

with the many demands on its time and resources, inexplicably has decided to focus on membership in an exclusive dining club

There is no allegation of fraud, and the floor price of the NFTs is remarkably stable compared to the broader NFT market, but the SEC has irrespective sued FlyFish and entered into a somewhat peculiar settlement deal on a no admissions basis under which FlyFish must destroy any remaining NFTs it holds, not accept any royalties for secondary sales of the NFTs, delete links to crypto exchanges on their website and social media, and pay a US$750,000 penalty.

The press release concerning the claim by the SEC merely asserts the NFTs were an “unregistered offering of crypto asset securities”, which is interesting as the SEC has just had to apologise to a Court for using the phrase “crypto asset securities” which has no meaning under law. There is no guidance or explanation of how the NFTs are said to have comprised securities other than the SEC alleging (with good grounds it seems) that:

Flyfish told investors that they could potentially profit from FlyFish’s efforts

The dissenting Commissioners assert the NFTs sold “are utility tokens, not securities”, and that:

A well-known artist who sells a limited set of numbered prints may be selling to a couple who wants to display her art in their home, or to someone who wants to turn around and sell it for a profit and is making a bet on the artist’s future. The intent of a buyer cannot transform a non-security into a security.

In a rare case of regulators making the case for less regulation, the dissenting Commissioners point out that:

The securities laws are not needed here, and their application is harmful both in the present case and as future precedent. The Flyfish NFTs were simply a different way to sell memberships. Why shouldn’t a chef be able to sell memberships to eat at her kitchen table and to collect royalties on resales of those memberships? NFTs offer a promising way to allow creative people—such as chefs, musicians, or visual artists—to monetize their talent and a potentially efficient way for selling access to experiences and communities.

The dissent casts a wide net in their closing comments, hooking the need for expensive lawyers in the web3 space:

Creative people should be able to experiment with NFTs without having to consult a high-priced tea-leaf reader—ahem, lawyer. The Commission can change its menu to include a healthy serving of guidance to give non-securities NFT creators the freedom to experiment.

A further school of no-admission settlements are expected as the US election looms and the present SEC rushes more regulation by enforcement before a possible change in the policy approach in the US. Other jurisdictions will hopefully learn that industry consultation and workable regulation is the best path to provide consumer protection and encourage innovation.

Written by Michael Bacina

SEC flips on the phrase with no definition: “crypto-asset securities”

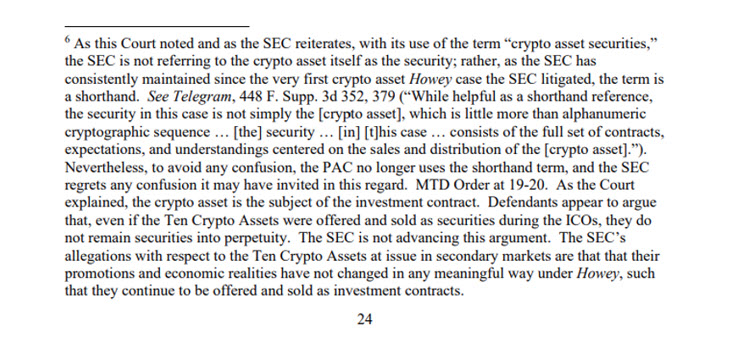

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has dumped the term “crypto-asset securities”, acknowledging a significant mis-step in their use of the phrase over a number of years. The admission, disclosed in an amended complaint against Binance on 12 September 2024, marks an important shift in language away from the regulator’s oft repeated stance that crypto-assets are somehow, and without further details of any kind ever being provided, inherently securities under US law.

The SEC clarified that the phrase “crypto asset securities” was not intended as an outright classification but was used as a ‘shorthand’, a decision they now ‘regret due to the confusion it caused’. This acknowledgment is a rare instance of the SEC conceding to criticism that it has overreached.

The SEC’s memorandum filed in support of the amended complaint sets out the SEC’s concession:

Despite the concession, the SEC has not backed down from its stance that the ten crypto-assets implicated in the Binance case were sold as securities when trading took place in secondary markets on the exchange. It is still unclear, due to the absence of any guidance from the SEC, when a crypto-asset is sold as a security or not.

At a Congressional hearing on the SEC’s approach to crypto, in September 2023 Rep. Ritchies Torres (D-NY) famously followed up a question about whether an investment contract (which is considered a security under US law) required a contract:

I [did] not go to MIT, but in the Bronx, if I ask whether any investment contract includes a contract, the answer is typically yes or no,

He also famously asked Mr Gensler if buying a Pokemon card was purchasing a security, to which Mr Gensler said “No”, but when asked if buying a Pokemon card on a digital exchange was a security Mr Gensler said “I’d have to know more.”

The timing of the SEC’s concession is particularly interesting, coming amid ongoing legal battles between the SEC and major players in the crypto world, including MetaMask and Coinbase. The notion that crypto-assets are inherently securities has come under increasing scrutiny by the Courts, including in the Ripple case where the New York court found that programmatic sales of the XRP token on exchanges were not securities transactions.

The SEC now appears to concede that its attempt to apply a blanket label to all crypto-assets as securities and create definitions without a proper logical basis for doing so must yield to the importance of clear definitions and rigorous legal analysis. While the concession is significant, it remains to be seen whether it will have any material impact on the SEC’s litigation strategy going forward with the SEC continuing to pursue a wide array of actions against centralised and decentralised platforms on the basis that they operated as unregistered broker dealers and exchanges (analogous to the New York Stock Exchange) by offering trading in crypto-assets.

Written by Steven Pettigrove, Michael Bacina and Luke Misthos