Blockchain Bites: RBA to test use cases for wholesale CBDC, Crypto industry rejoices SEC rule rejection and Chair resignation, DAOs should consider wrapping up to avoid unlimited liabilities, SEC becomes defendant in lawsuit against “regulatory overreach”, Australian superior court finds Bitcoin is property

22/11/2024

Steven Pettigrove, Jake Huang, Luke Higgins and Luke Misthos of the Piper Alderman Blockchain Group bring you the latest legal, regulatory and project updates in Blockchain and Digital Law.

RBA announces Project Acacia to test use cases for wholesale CBDC

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has released a consultation paper outlining a joint research initiative by the RBA and the Digital Finance Cooperative Research Centre (DFCRC) to explore how different forms of digital money and associated infrastructure could support the development of wholesale tokenised asset markets in Australia.

The consultation is the public phase of a project dubbed Project Acacia, which builds on the lessons from the RBA’s central bank digital currency (CBDC) pilot last year, by focusing on opportunities to uplift the efficiency, transparency and resilience of wholesale markets through tokenised money and new settlement infrastructure. At the Intersekt Fintech Conference in September, the RBA announced details of the project, which reflects its strategic commitment to exploring a wholesale, rather than a retail, CBDC.

Project Acacia overview

As mentioned, the project is divided into two main phases:

Phase 1 – Conceptual Research: This was undertaken by the RBA and DFCRC during the first half of 2024 as an initial desktop research phase in which different models for the settlement of tokenised asset transactions were identified and evaluated.

- The focus was on exploring how different settlement models – utilising various forms of digital money and associated infrastructure – could facilitate the delivery-versus-payment (DvP) settlement of tokenised asset transactions (i.e. a transaction between a buyer and seller whereby the transfer of a tokenised asset occurs if and only if the associated payment has been made). Five settlement models were identified and then subject to a structured evaluation.

Phase 2 – Experimentation: The current phase will involve practical experimentation to test the identified models and approaches. The RBA and DFCRC, in collaboration with selected industry participants, propose to develop and test prototypes of one or more models for settlement of wholesale tokenised asset markets.

- This exercise will be framed by use cases proposed by industry. This may involve the RBA issuing a pilot wholesale CBDC and/or private sector parties issuing deposit tokens or other forms of tokenised money (e.g. reserves-backed digital currency or stablecoins), depending on the use cases proposed by industry stakeholders and selected for development and testing.

- It is envisaged that the work would be supported by industry stakeholders, working collaboratively, in roles such as tokenised asset issuers, investors and token platform market operators.

- The purpose of Phase 2 is to test some of the findings of the conceptual research in Phase 1 by overlaying the business objectives of industry stakeholders, and to explore more deeply questions of technology design, risk management, governance and regulation associated with one or more of the settlement models evaluated in Phase 1 and/or alternative models nominated by industry participants.

- Industry stakeholders are invited to provide feedback on how and where the applied research effort in Phase 2 could be directed, by nominating use cases they have an interest in exploring in collaboration with the RBA and DFCRC and the research questions they wish to focus on.

- The RBA and DFCRC do not intend to set up or make available a simulated or pilot tokenised asset platform or trading venue for Phase 2. Industry participants will need to establish these platforms to suit their needs.

- Industry participants will bear their own costs for the conception, design, development, implementation and execution of their proposed use cases in Project Acacia.

- The RBA and DFCRC, in collaboration with relevant regulatory agencies (ASIC, APRA and AUSTRAC, as applicable), will work with interested parties to establish what licences or regulatory relief those parties may need to participate in the project. Use case proposals will be selected for development and testing and announced by the RBA and DFCRC only after licences or regulatory relief (where required) are obtained.

Industry Advisory Group

The RBA and DFCRC also intend to establish an ‘Industry Advisory Group’ of selected industry experts, to support Phase 2 of Project Acacia. The Industry Advisory Group will receive periodic updates on Project Acacia and will have an important role providing advice on the project pathway, findings and future research opportunities. It will be an advisory forum and will not make decisions with respect to the management or running of the project. It will be chaired by a representative of the DFCRC and will report to the Project Acacia Steering Committee.

Next Steps

The RBA has invited industry stakeholders to:

- Respond to the consultation questions – by completing Part 1 of the Response Template in Appendix A of the paper.

- Register their interest in participating in the experimental research phase of Project Acacia in 2025 – by completing Part 2 of the Response Template in Appendix A of the paper.

- Register their interest in joining the Industry Advisory Group for Project Acacia – by completing Part 3 of the Response Template in Appendix A of the paper.

Submissions are due by Wednesday, 11 December 2024.

Conclusion

Project Acacia follows the RBA’s successful CBDC pilot in 2023 with a view to unlocking the potential benefits of tokenised markets for the Australian economy which the DFCRC has estimated at up to $12 billion in value per annum.

The project represents a significant step towards understanding and implementing digital money in wholesale markets. The collaboration between the RBA, DFCRC, and industry stakeholders aims to develop a robust and efficient framework for digital asset transactions, with a view to ensuring that Australia’s financial infrastructure remains globally competitive with the likes of Singapore (which has operated a long running tokenisation pilot called Project Guardian) and ready to embrace the digital economy.

The Piper Alderman Blockchain Group advises on asset tokenisation projects and can assist industry stakeholders interested in participating in Project Acacia with preparing their expressions of interest and exploring necessary licensing approvals and relief.

Written by Jake Huang and Steven Pettigrove

Crypto industry rejoices SEC rule rejection and resignation of SEC Chair

It’s a huge day for the crypto industry, with bitcoin hovering just under US$100,000, the SEC Chair Mr Gary Gensler has announced his resignation, effective 20 January 2025, and the US District Court of Northern Texas has struck down a much criticised dealer rule which was enacted earlier this year. These represent an ongoing windback of the path of regulation by enforcement run by the US SEC against the crypto industry, and creates space for sensible rulemaking and consultation.

Bye bye bye (bye bye)

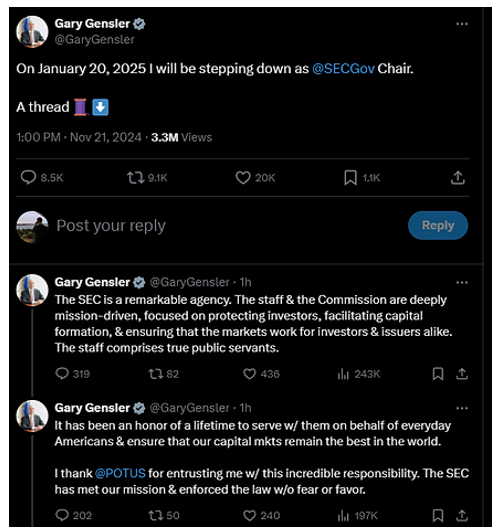

Rumours have been flying around as to who President-elect Trump would seek to appoint as Chair of the SEC. At Bitcoin Nashville President Trump announced he would “fire Gary Gensler” on day one of his Presidency. That Mr Trump doesn’t actually have power to do that (a President can only fire the Chair of the SEC with cause) is now moot, as Mr Gensler took to Twitter to confirm his resignation, which came after a recent speech which was interpreted as a farewell address:

Mr Gensler’s departure press release paints as rosy a picture as possible about Mr Gensler’s enforcement actions against crypto, first pointing the finger at former Chair Clayton:

Under Chair Gensler, the Commission continued the work Chair Jay Clayton began to protect investors in the crypto markets. During Chair Gensler’s tenure, the agency brought actions against crypto intermediaries for fraud, wash trading, registration violations, and other misconduct.

then moving on to raise statistics seeking to cast crypto in a negative light and justify the regulation by enforcement actions undertaken by Mr Gensler’s SEC:

In the last full fiscal year, according to the SEC’s Office of the Inspector General, 18 percent of the SEC’s tips, complaints, and referrals were crypto-related, despite the crypto markets comprising less than 1 percent of the U.S. capital markets. Court after court agreed with the Commission’s actions to protect investors and rejected all arguments that the SEC cannot enforce the law when securities are being offered—whatever their form.

It’s unclear within the 18% what the numbers were between tips, complaints and referrals which might indicate how many referrals were from the industry seeking clarity and how many might have related to single events (for example it’s fair to assume a great many complaints were received by the SEC over the FTX collapse but the SEC only uses “Crypto-related” as a catch all definition – this category stands in stark contrast to other complaint categories which seem function, not industry, oriented).

Protos.com tried to work out the SEC success rate in their enforcement actions, finding that in the 116 actions commenced (accurate to 4 June 2024), naming 260 different crypto companies, the SEC settled or won 95 of those cases. It is important to note the SEC is permitted to enter into “no admission of wrongdoing” settlements, which permit defendants to avoid the risk of a judgment by making an agreed payment.

Critics might note that the 116 lawsuits would have been unnecessary had there been clear rule making and a pathway to compliance, but it cannot be said the SEC has not overwhelmingly run successful prosecutions, if success is measured by how many defendants settle or lose. However there have been some very significant losses by the SEC, including in trying to block Bitcoin ETFs, which was found to be ‘arbitrary and capricious’. We now turn to the most recent SEC loss:

End of Dealer Rule

If the industry wasn’t pleased enough at a possible end to Mr Gensler’s tenure, the US District Court in North Texas published a summary judgment which rejected the SEC’s Dealer Rule. As we have written, the new Rule sought to put forward two new qualitative and non-exhaustive criteria to establish “dealer” status for persons providing liquidity in securities markets (including what the SEC calls “crypto securities” a phrase which has now been withdrawn):

- Expressing Trading Interest Factor: regularly expressing trading interest that is at or near the best prices on both sides of the market for the same security, and that is communicated and represented in a way that makes it accessible to other market participants; or

- Primary Revenue Factor: earning revenue primarily from capturing bid-ask, by buying at the bid and selling at the offer, or from capturing any incentives offered by trading venues to liquidity-supplying trading interest.

The effect of the Rule would have been to bring nearly all DeFi and crypto activity within the SEC’s “dealer” definition and require registration, which is impossible for most, if not all, crypto businesses because the SEC does not permit it to occur.

The District Court’s summary judgment decision was particularly scathing about the Rule, opening with:

A regulator’s temptation may be to put every corner of the market under a regulatory spotlight.” When engaging in that temptation causes an agency to act beyond its authority, the judiciary is obligated to thwart that action

And going on to note the incredible breadth of the “dealer rule” and lack of any prior extension:

many of the world’s largest, most prominent market participants, including the Federal Reserve, may have been operating unlawfully as unregistered securities “dealers” for 90 years without anyone—including the Commission—having previously noticed. Operating as an unregistered dealer under the Exchange Act is a felony.

The court considered the long history of the definition of “dealer” in the United States and found that the “dealer rule” exceeded the SEC’s statutory authority. The court found that a full vacation of the Rule, not a limited remand as sought by the SEC, would be appropriate, agreeing with Commissioner Peirce’s dissent that:

the Rule “obliterates” the regulatory scheme as “the Commission and market participants have read it for decades.

Take aways

The combination of rule rejection and resignation is further evidence of a dramatic shift in the US, one which seems to have prompted other jurisdictions, including the UK, to message more supportive crypto policies (with one UK politician noting the UK had been “regulating for risk instead of regulating for growth” in digital assets) but it remains to be seen if the message is being heard in other advanced financial services jurisdictions.

Written by Michael Bacina

Unlimited liability? Naked DAOs might want to consider wrapping up…

A judge in the Northern District of California has caused concern in the crypto community, rejecting a motion brought by a “DAO adjacent” company seeking to dismiss proceedings brought by a token purchaser who lost money on a small token purchase.

The background to the matter is that Lido DAO issued tokens, as many crypto projects do. However, Lido DAO did not have any kind of legal wrapper around the DAO, such as a foundation company, which have become a common vehicle to permit DAOs to engage in contracts with other parties.

One of the token purchasers, who bought and sold a small number of tokens, claims to have lost money in doing so and has sued Lido DAO together with several prominent crypto venture capital funds, seeking to represent every token purchaser who lost money, alleging that Lido DAO should have been registered under the US securities laws and that all owners of tokens are in a general partnership with unlimited liability.

After the court found that Lido DAO had been properly served (itself an interesting question as a DAO typically has no legal personality at law), Lido DAO held a governance vote to authorise the engagement of a law firm by a DAO adjacent company in order to file and argue a motion seeking to dismiss the legal proceedings on the basis that the Plaintiff was trying to sue software and not an entity (along with other arguments).

Prominent crypto lawyer Stephen Palley was engaged to argue the motion and a number of other leading crypto lawyers and projects filed amicus briefs in support of the motion to dismiss. These kinds of interlocutory motions are difficult to win as the mover must show there is no prospects of the action being successful, or that there is some flaw so fatal to the case it should not proceed further. The court hearing revealed a skeptical judge who challenged why the Plaintiff had not objected to the motion being filed by an entity which wasn’t Lido DAO.

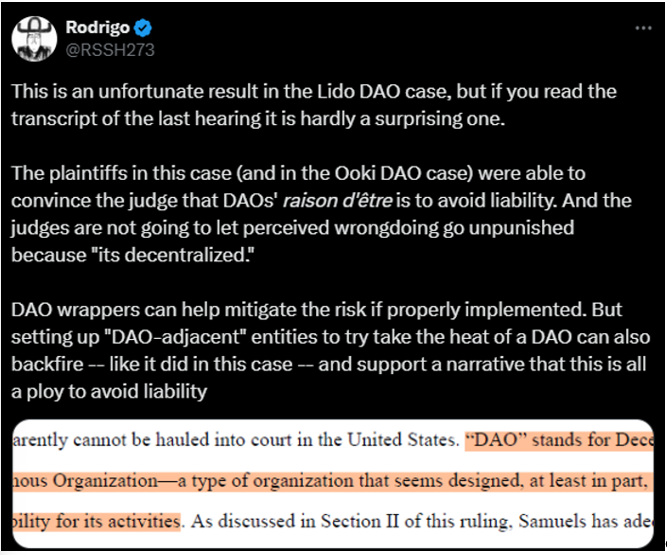

The decision of the court rejecting the motion to dismiss included comments which have concerned some in the crypto community, including the defendants:

“DAO” stands for Decentralized Autonomous Organization—a type of organization that seems designed, at least in part, to avoid legal liability for its activities.

Lido’s alleged actions are not those of an autonomous software program—they are the actions of an entity run by people

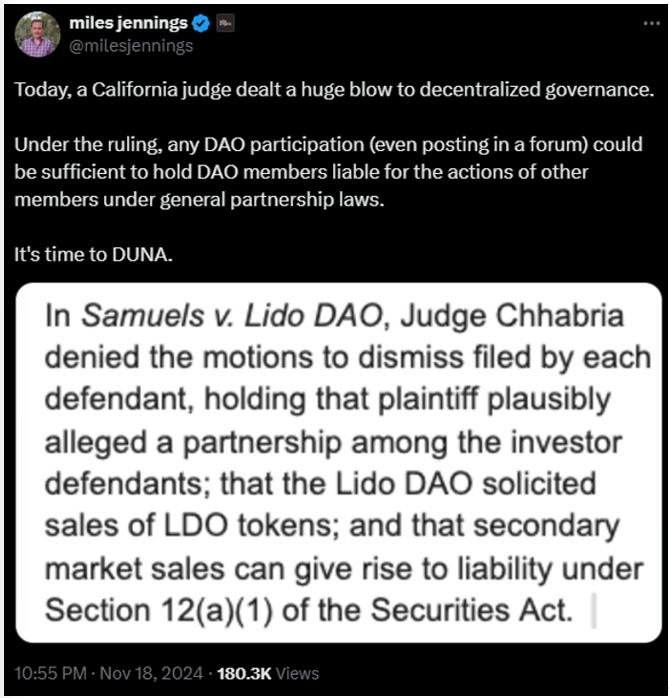

In response, Miles Jennings, General Counsel of a16z posted on X that this was “a huge blow to decentralised governance”:

Rodrigo Seira from Cooley noted the way that the Plaintiffs had argued the case was by suggesting DAOs were set up to avoid liability:

Take aways

While the decision is not binding precedent for other cases and motions to dismiss are difficult to win in many circumstances, the take away is that DAOs, and their token holders and VCs who buy tokens, and which are seeking to operate as “pure software” without a legal wrapper, are on heightened risk of litigation in the USA and other jurisdictions with all the expense and distraction that entails.

The motion alone cost the Lido DAO treasury at least USD$200,000, when the costs of establishing a wrapper entity, such as a Cayman Island foundation, one of the most popular forms of crypto structures, would have been well below that sum.

The ongoing costs of the litigation, not just for Lido DAO, but also for defendants Paradigm, a16z and DragonFly, will be substantial and remove funds which could have supported further projects.

The clear takeaway is that a legal wrapper is increasingly not an optional item for DAOs, but is really a necessity from the start of a DAO’s establishment.

Written by Michael Bacina

Disclosure: the writer works at Travers Thorp Alberga and has been advising DAOs to be wrapped, including with Cayman Foundations, for many years.

Crypto enforcement oriented SEC finds itself now a defendant in 18 state lawsuit against “regulatory overreach”

In a huge reversal for the Securities & Exchanges Commission (SEC), 18(!) states have joined with advocacy group DeFi Education fund in asking a Federal Court to restrain the SEC from bringing further actions against crypto-company defendants, saying that the lawsuits brought by the SEC under Chair Gensler’s:

‘crypto policy’ is ‘unlawful executive action’

The Attorney General of Kentucky, where the lawsuit was filed, was quick to highlight the media picking up the story:

The lawsuit’s filing argue:

the SEC has sought to unilaterally wrest regulatory authority away from the States through an ongoing series of enforcement actions targeting the 3 digital asset industry, premised on the theory that practically all purchases and sales of digital assets are “investment contracts”—and so qualify as securities transactions under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Exchange Act of 1934—because some digital asset buyers expect those assets to increase in value based on the efforts of their creators…and subjects the entire digital asset industry to a single ill-fitting regime that Congress enacted for an entirely different kind of financial instrument.

This is a reference to the famous Howey test which the SEC has applied very expansively to crypto-assets, previously calling them ‘crypto asset securities’ but pivoting recently to now call them ‘crypto-assets sold as securities’. Importantly the lawsuit highlights the key policy issue which does not get as much light as it should – it is presently impossible for crypto-asset projects issuing tokens to comply with existing financial services laws.

Those who are in favour of bespoke regulation argue that consultative rule-making should be undertaken to address this issue and provide a pathway to compliance. Those against either ignore the issue, leading to criticism of Chair Gensler’s invitation to “come in and register” given registration is impossible, or argue that crypto projects must modify their entire business operations to retrofit into the existing laws, which would, projects argue, mean removing everything novel or innovative about their operations / projects.

The lawsuit goes on to argue:

The SEC’s logic would empower the agency to regulate (and displace State regulation of) not only all transactions in digital assets but also a boundless array of other assets as well, from collectibles to luxury goods and beyond.

There is plainly a delicate line to be walked, the use of blockchain or crypto technology should not permit a product which is presently regulated from escaping regulation by becoming tokenised, but nor should that choice of technology transform a digital good into something which cannot comply with securities regulations.

Regulators have been grappling with this problem for some time, trying to avoid an erosion of control over traditional financial markets while recognising crypto-systems are creating a ‘financialisation’ of products which was not previously possible.

The risks posed by crypto-systems also differ in fundamental ways from those in traditional financial marketplaces, all of which highlights the urgent need for bespoke and fit for purpose regulation which is innovation enabling, so as to protect consumers and investors who clearly want to access this market. Recent comments from the ASIC annual forum in Australia show that there is limited understanding of crypto-products, with the ASIC Chair raising the “greater fool theory” and the Reserve Bank of Australia Chair saying she doesn’t understand bitcoin. The mantra of “same activity, same risk, same regulation” has been raised as a guiding principle for crypto-asset regulation, and this time-tested approach is an excellent guide, so long as there is sufficient fit to the unique technical aspects of crypto-assets which simply do not function the same as traditional products. For example, in 2002 Coinbase identified 50 questions needing guidance or exemptions under the US regulatory framework when crypto-assets were being considered and sought engagement and rule-making. That has been rejected by the SEC so far, leading to Coinbase suing the SEC to try and require rulemaking. In Australia, proposals for licensing of crypto exchanges do not address when tokens may or may not be financial products, and there is no guidance given as to how a token which IS a financial product could be offered for sale in a way compliant with existing laws.

It is unfortunate that the situation of an absence of rule-making coupled with regulation by enforcement has led to a point where US states must sue the Federal regulator but with the recent US election and a likely change in leadership at the SEC there seems to be a focus on lawsuits where fraud has occurred, rather than a regulation-by-enforcement approach continuing. Which jurisdictions follow this potential change will be revealing as crypto continues to grow and regulators must make hard decisions around what controls they can put around access to the crypto markets.

Written by Michael Bacina

Australian superior court finds Bitcoin is property

In an Australian legal first, Justice Attiwill of the Supreme Court of Victoria has determined that a person’s interest in Bitcoin is property. This case is ground-breaking, as it is the first superior court proceeding where an Australia court has found that a cryptocurrency possesses all characteristics of property. It brings Australia in line with other common law jurisdictions such as the UK, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Singapore in recognising cryptocurrency as property at common law.

In Re Blockchain Tech Pty Ltd [2024] VSC 690, the plaintiffs alleged that 36 Bitcoin (which are worth over AUD5 million based on market value current as at the date of this article) had been transferred to the first defendant on bailment and that Blockchain Tech was entitled to immediate possession of the same.

It was alleged that a further 25 Bitcoin which had been transferred from Blockchain Tech to an exchange to be dissipated for working capital purposes was held on trust by the first defendant as trustee. The plaintiffs argued that the defendant trustee had failed to fully account for the sums dissipated which had been partly misappropriated for personal expenses.

Citing recent interlocutory judgments in Australia, and substantive judgments in New Zealand and England and Wales, Attiwill J decisively ruled that a person’s interest in Bitcoin (being intangible) is property as it satisfies the four classic criteria for property under the common law Ainsworth test – that is:

- identifiable by subject matter;

- identifiable by third parties;

- is capable of assumption by third parties; and

- has some degree of permanence or stability.

In elaborating on his reasons, Attiwill J stated:

First, it is necessary to identify ‘the thing’. The thing is Bitcoin. It is an electronic coin.

Second, an interest in Bitcoin is also identifiable by third parties…the public key identifies an address of Bitcoin at that address on the shared public ledger. A person has the power to control and deal with the Bitcoin and to exclude third parties from accessing or dealing with it.

Third, a person’s interest in Bitcoin has a degree of permanence or stability. Bitcoin are recorded on the shared public ledger…this contains the ‘entire life history of a cryptocoin’…Bitcoin are held at a certain digital address. Bitcoin remain stable at the address until there is a transaction concerning those Bitcoin.

Fourth, although a Bitcoin transfer transaction does not involve the ‘transfer’ of a person’s interest in the Bitcoin, this does not mean that an interest in Bitcoin is not property. This is because alienability is not an indispensable attribute of property.

Fifth, a person’s interest in Bitcoin may be readily distinguished from a mere interest in information, including electronic data.

[384] – [388], emphasis added

In his reasoning, Attiwill J endorsed Justice Jackman’s extra-judicial comments in his speech “Is cryptocurrency property?” earlier this year, and cited a UK draft bill which in turn was based on a proposal advanced by the UK Law Commission, all supporting judicial and legislative efforts to recognise cryptocurrencies (or rights in cryptocurrencies) as property.

Attiwill J’s decision departs from the UK Law Commission’s position that crypto-assets do not fit neatly into the existing categories of personal property (i.e. are things in possession or things in action), and which recommended the implementation of a third category of personal property called “data objects”. Rather, Attiwill J said a person’s interest in Bitcoin is

not a chose in possession as it is intangible. It cannot be possessed. It is a chose in action.

This is because

it is well established in Australia that a chose in action comprises a heterogeneous group of rights which have only one common characteristic in that they do not confer the present possession of a tangible object. That is the case with Bitcoin.

On the basis that an interest in Bitcoin is property, Attiwill J went on to find that the 25 Bitcoin transferred to the first defendant were held on trust. In the circumstances, Attiwill J held that Blockchain Tech was entitled to equitable compensation on the basis the defendant had failed to fully account for the dissipated Bitcoin. However, he held that the trustee’s obligation had been to dissipate the Bitcoin and account for the value of the same at the price at the time (and not at today’s prices).

Meanwhile, Attiwill J rejected the argument that Bitcoin was capable of being held on bailment as it is an intangible form of property.

Attiwill J’s judgment represents a significant judicial precedent in relation to Bitcoin and is likely to pave the wave for similar recognition of other cryptocurrencies as property. The decision helps to clarify the rights of Bitcoin holders while also having potential implications for third party custodians subject to their applicable terms and conditions. The recognition of Bitcoin as property also expands the range of remedies available to persons seeking to trace and recover misappropriated crypto-assets.

The Victorian Court will now hear from the parties on the precise form of orders. While the case may be appealed, the detailed analysis by Attiwill J and support from overseas authorities are likely to be difficult to overcome.

Written by Jake Huang, Steven Pettigrove and Michael Bacina