Koninklijke v Cantarella: An Instant Coffee Clash

07/01/2025

In a recent Federal Court decision, Wheelahan J dismissed claims that Cantarella’s Vittoria coffee jar infringed the famous Moccona coffee jar that is the subject of a registered shape trade mark. The case provides a useful insight into what is needed for a shape to be a “badge of origin” and the difficulties with enforcing shape trade marks.

Background & Material Facts

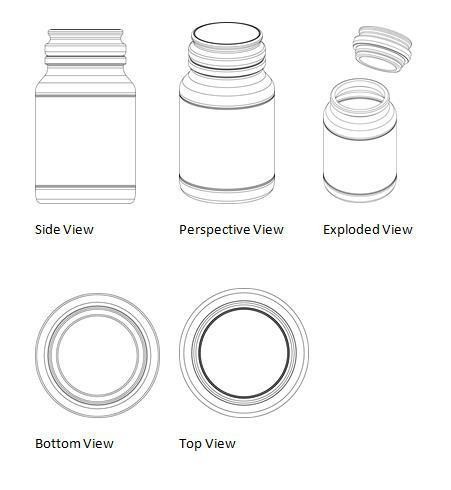

The first applicant, Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV (KDE), is the owner of Australian Trade Mark Registration Number 1599824 for the following shape trade mark:

(KDE Shape Mark).[1]

(KDE Shape Mark).[1]

The KDE Shape Mark has a priority date of 7 January 2014 and is registered in Class 30 for coffee and instant coffee.

The second applicant, Jacobs Douwe Egberts AU Pty Ltd (JDE AU), sells instant coffee in Australia under the well-recognised brand name “Moccona”. JDE AU sells Moccona-branded instant coffee in a glass jar, as shown below.[2]

The respondent, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), also sells instant coffee, under the trade mark “Vittoria”.[3] In August 2022, Cantarella launched a 400-gram instant coffee product in the jar that is shown below.[4]

The applicants alleged that Cantarella’s use of the 400-gram Vittoria jar infringed the KDE shape mark pursuant to section 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA).[5] The applicants also alleged that Cantarella had contravened various provisions of the Australian Consumer Law and that it had engaged in the tort of passing off.[6]

By way of cross-claim Cantarella sought to cancel the KDE Shape Mark from the Trade Marks Register on a number of grounds.[7] Of note were Cantarella’s arguments that:

- as at the priority date of the KDE Shape Mark, the mark lacked distinctiveness; and

- the Registrar of Trade Marks accepted the application for registration of the KDE Shape Mark on the basis of representations that were false in material particulars, and that the mark was entered on the Register as a result of false suggestion or misrepresentation.[8]

Findings

Wheelahan J dealt first with Cantarella’s cross-claim.

Lack of Distinctiveness

Under section 41 of the TMA, an application for a trade mark registration must be rejected if the mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of others.[9] This is also a ground for cancellation of a trade mark by operation of sections 57 and 88 of the TMA.[10]

His Honour highlighted that for shape marks, functional purposes of the shape will be incapable of distinguishing goods or services unless something “special” or “extra” is added for the shape to function as a trade mark.[11] This is determined by assessing the shape mark by reference to a “spectrum” of shapes from those that are simply functions to those that are “non-functional.”[12] As noted in Kenman Kandy, enabling a registration of a trade mark that gives an owner a monopoly over “functional features” would radically shift trade mark law in Australia.[13]

In the case of the KDE Shape Mark, his Honour considered there to be both functional and aesthetic purposes.[14] Functional features included the cylindrical shape, the opening and the stopper-type lid, while aesthetic features included the double-tiered lid and the slope of the shoulder between the body of the jar and the lid.[15]

However, the aesthetic features of the KDE Shape Mark were not sufficiently distinctive as they were similar to the features of other pre-existing jar designs.[16] Therefore, his Honour concluded that the KDE Shape Mark was not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish KDE’s goods from the goods of others.[17]

Notwithstanding this, Wheelahan J considered KDE’s extensive use of the KDE Shape Mark prior to the priority date of the mark, and held that the KDE Shape Mark had acquired distinctiveness through that use.[18]

Of significance was the number of Moccona advertisements that solely promoted the shape of the jar.[19] One such example was a 2008 advertisement entitled “Cinderella” which depicted a man in possession of a Moccona jar lid on a quest to find the “perfect match” coffee jar.[20]

His Honour concluded that the applicants had developed a significant association between the Moccona coffee products and the jar shape in which those products were sold. As a result, the KDE Shape Mark was distinctive.[21]

False Representations

Under section 62(b) of the TMA, the registration of a trade mark may be cancelled if the Registrar accepted the application on the basis of evidence or representations that were false in material particulars.[22] Additionally, registration may be cancelled if a trade mark was entered onto the Register “as a result of fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation”.[23] Wheelahan J dealt with these two grounds together.

The basis of Cantarella’s claims was that, during examination for registration of the KDE Shape Mark, the applicants made various false statements.[24] One such example was a statement made that coffee had been sold under the trade mark MOCCONA since 1960 and since that time, it had been sold “in a unique and readily identifiable jar”. [25]

Wheelahan J concluded that this statement was in fact false, as Moccona coffee had not been sold in a jar the subject of the KDE Shape Mark until late 1977.[26] However, his Honour did not consider this statement to be false in material particulars, as there was no evidence that indicated the Trade Marks Examiner would probably have decided not to register the KDE Shape Mark, had it not been for the false statement.[27] This was because much of the Examiner’s reasoning to allow registration of the KDE Shape Mark focussed on evidence of use from 2008 onwards.[28]

In summary, Wheelahan J refused to cancel the KDE Shape Mark from the Trade Marks Register.

Infringement

In determining whether Cantarella infringed the KDE Shape Mark, Wheelahan J first considered whether Cantarella had used the shape of the 400-gram Vittoria jar “as a trade mark.[29] This is because, for an infringement claim to be made out under section 120 of the TMA, a person must be using, as a trade mark, a sign that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the registered trade mark in relation to the goods or services the subject of the registration.[30] Use as a trade mark is use as a “badge of origin” in the minds of consumers.

Referring again to the “spectrum” of shapes from “purely functional” to “non-descriptive and non-functional”,[31] his Honour considered the shape of the Vittoria jar to be plain and without any aesthetic embellishments.[32] Further, the advertisements relating to the Vittoria jar did not draw any express attention to the shape of the jar itself.[33] The jar was ultimately functional in use, with Wheelahan J considering that the focus by Cantarella was on the premium materials used in the jar, rather than its shape. Therefore, Cantarella had not used the Vittoria jar as a trade mark and the applicants’ infringement claim failed.[34]

While not necessary to decide, Wheelahan J also considered whether the Vittoria jar was deceptively similar to the KDE Shape Mark.[35] His Honour considered that a notional buyer with an imperfect recollection of the KDE Shape Mark would recall its ‘cylindrical body with, in roughly its top third, a shoulder that slopes to a thick neck ring surmounted by a two-tiered lid.’[36] In contrast, the 400-gram Vittoria jar had a much taller body with a single disk lid that is wider than the neck of the jar.[37] His Honour concluded that there was no risk that the notional buyer would be caused to wonder whether instant coffee sold in the Vittoria jar shape had the same commercial source as coffee sold in the KDE Shape Mark.[38] Therefore, the Vittoria jar was not deceptively similar to the KDE Shape Mark.[39]

Takeaways

This case serves as a useful insight into the requirements for the registration and enforcement of a shape mark. The shape must have some non-functional “extra” or “special” feature in order to be capable of distinguishing the trade mark applicant’s goods or services. Additionally, extensive use of the shape mark will assist in acquiring distinctiveness, though care must be taken to ensure use draws attention to the shape of the mark and asks consumers to use it as a point of distinction from the goods of other traders.

Piper Alderman has a nationally recognised practice in intellectual property enforcement and protection, with experience in all jurisdictions. Please contact Tim O’Callaghan and his team if you require intellectual property advice.

[1] Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1277 [2], [4] (‘Koninklijke v Cantarella’).

[2] Ibid [3].

[3] Ibid [7].

[4] Ibid [9].

[5] Ibid [10].

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid [11].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 41 (‘TMA’).

[10] Ibid ss 57, 88.

[11] Koninklijke v Cantarella (n 1) [255] citing Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA; 100 FCR 90 [16]; Kenman Kandy Australia Pty Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks [2002] FCAFC 273, [137].

[12] Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 605 [62] – [64].

[13] Kenman Kandy Australia Pty Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks [2002] FCAFC 273, [137]. See also RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10.

[14] Ibid [260]-[262].

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid [267].

[17] Ibid [257].

[18] Ibid [292].

[19] Ibid [298].

[20] Ibid [299].

[21] Ibid [306].

[22] TMA (n 9) s 62(b).

[23] Ibid s 88(2)(e).

[24] Koninklijke v Cantarella (n 1) [375], [379].

[25] Ibid [375].

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid [421].

[28] Ibid [419]-[420].

[29] Ibid [457].

[30] TMA (n 9) s 120(1).

[31] Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 605 [62] – [64].

[32] Koninklijke v Cantarella (n 1) [460].

[33] Ibid [463].

[34] Ibid [478].

[35] Ibid [479].

[36] Ibid [501].

[37] Ibid [502].

[38] Ibid [496].

[39] Ibid [506].